Access to Justice Denied:

Parental, Family and

Organized Child Abduction in Oregon

By Sean Aaron Cruz

April 12,

2013

Testimony in support

of House Bill 2014, sponsored by

State Representatives Alissa Keny-Guyer, Brent Barton, Chris Garrett, and Wayne

Krieger

“Please tell Sean that I also wish him

the best. I have also followed his career and believe his personal experience

has given him the wisdom and the moral authority necessary to make a real

difference in making Oregon

safer for our children.” –Hon. Judge James L. Fun, Washington County

Circuit Court, January 24,

2007

Access to Justice Denied: Parental,

Family and

Organized Child Abduction in Oregon

I. Oregon’s Custodial Interference I and II

statutes

A. The four statutory barriers to

justice

1. “A person”

exceptions

2.

The definition of “protracted”

3.

“…a substantial risk of illness or

physical injury”

4. A crime in progress

II. Overview of

access to justice in Oregon

III.

Finding legal assistance in the wake of an abduction today

A.

The Oregon State Bar

B. The Oregon Judicial Department

C. The Oregon State

Police Missing Children Clearinghouse

IV. The roots of

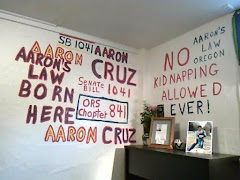

Senate Bill 1041 Aaron’s Law (2005)

A. The 1996

abduction of Aaron Cruz and his siblings

B.

Legislative history of Aaron’s Law

1.

Reporting the crime to the Legislative Assembly

2.

Take Root – Adults who were abducted as children speak

3.

The 2004 Task Force on Parental and Family Abductions

a. No numbers

b. A broad lack

of awareness

c. Some parents

use their children as weapons

d.

Long-lasting trauma, injury and damage

e. Damage similar to sex

crimes against the child

4.

“Burning Issues in Access to Justice”

5.

Aaron’s Law in statute: ORS 30.868

V. The principles of

Aaron’s Law

A. Victims

in control, not The System

B. Who you

serve and 142 reasons why

C. Domestic

violence exception

D. Counseling for resolution and

deterrence

E. The

child victim becomes an adult

F. Aaron’s

Law and child trafficking

VI. Case Study:

Aaron’s Law and the Kyron Horman abduction

A. “There is no case like this.”

B. Meeting

the criteria

VII.

Attitudes as Obstacles

“Your

children will find you some day (Don’t worry be happy)”

I. Oregon’s Custodial

Interference I and II statutes

Four significant barriers to access to justice and to

prevention and resolution of child abduction cases lie in the statutes

themselves and in how Oregon law enforcement agencies and the Family and

Criminal Law systems interpret the language.

ORS

163.245: “A person commits the crime of custodial interference

in the second degree if, knowing or having reason to know that the person has

no legal right to do so, the person takes, entices or

keeps another person from the other person’s lawful custodian or in

violation of a valid joint custody order with intent to hold the other person permanently or for a

protracted period.”

ORS

163.257: “A person commits the crime of custodial interference

in the first degree if the person violates ORS 163.245 and:

(a)

Causes the person taken, enticed or kept from

the lawful custodian or in violation of a valid joint custody order to be removed from the state; or

(b)

Exposes that person to a substantial risk of illness or

physical injury.”

A. Four statutory barriers

to justice

1. “A person” exceptions: The statutes make no exceptions for

the other parent, family members or hangers-on, members of a church

congregation enforcing a shunning or any other organized group of persons

acting with criminal intent. In actual practice, however, when a parent is

involved in the abduction, law enforcement and the Family Law and Criminal Law

systems appear to follow a policy of ignoring the other persons who have

violated the statute. This highly selective enforcement of the Custodial

Interference statutes contributes to the incidence of child abductions. Since

it is so unlikely that nonparental persons will be held accountable for their

crimes, the statute has little deterrent value, hence the high incidence of

parental and family abductions.

HB 2014 should result

in an understanding of how and why decisions to make exceptions to the statute

are made at the local level, providing the 2014 Legislative Assembly with the

opportunity to consider establishing a state policy.

2. “Permanently or for a protracted period”: There appears to be no statewide policy or published local law

enforcement directive regarding when the threshold of “protracted” is reached

and the Custodial Interference statute is triggered. The dictionary definition

of “protracted” is “prolonged.” The absence of a clear definition of

“protracted” in statute makes it difficult for law enforcement to act, creating

a systemic barrier to the swift resolution of these cases.

HB 2014 should

result in an understanding of the range of interpretations of this statute

among local law enforcement jurisdictions across Oregon, providing the 2014 Legislative

Assembly with the opportunity to consider enacting a statewide policy regarding

this critical definition.

3. “Exposes that person to a

substantial risk of illness or physical injury.” The real injuries a child victim

suffers in an abduction is not recognized in current statute. Although the

Legislative Assembly has adopted a policy of mental health parity in health

insurance coverage, it is not clear that parity applies to the “substantial

risk of illness” component of the custodial interference statutes, and the term

“physical injury” explicitly fails to recognize the mental and emotional trauma

victims suffer.

The 2004 Senate

President’s Interim Task Force on Parental and Family Abductions reported: “…the

injury a child receives, when the child has been abducted by one of the child’s

parents, does not necessarily include physical injury. The injury is more in the nature of mental trauma or mental injury. Nonetheless,

the injury is real and may be even more long lasting and damaging than physical

injury.”

Failing to recognize the serious nature of these nonvisible

injuries contributes to inaction by law enforcement and the court systems.

HB 2014 should be

expected to reveal a deficiency in how abductions are prioritized by law

enforcement and both the Family Law and Criminal Law systems. The report will

provide the 2014 Legislative Assembly with an opportunity to establish a clear

policy regarding the definition of “illness” and “injury” in respect to mental

health parity.

4. “A crime in progress”: The Custodial Interference statute does not

take into account the fact that abductions are “continuing” crimes. The trauma

and loss that victims suffer increases over time, yet law enforcement and both

the Family Law and Criminal Law systems routinely fail to treat these case as

crimes in progress, which is exactly what they are.

HB 2014, coupled with the Final Report of the Parental and Family Abduction

Task Force, should provide the 2014 Legislative Assembly with a better

understanding of the Custodial Interference statutes and offer ideas to better

protect the interests of Oregon

children and their families.

II. Overview of access to

justice in Oregon

For more than sixteen years, the Oregon Legislative Assembly

has considered the serious problem of public access to competent legal services

in the Family Law system:

“In a final report given to

the December, 1997 Legislative Assembly, the Oregon Task Force on Family Law

articulated the continued unmet and acute demand for assistance dealing with pro se

litigants in the court systems. At the request of the Task Force, the

Legislature created the Oregon Family Law Legal Services Commission. The charge

to this group was to evaluate and report on “how courthouse facilitation and

unbundled legal services might enhance the delivery of family law legal

services to low and middle-income Oregonians.” During the next four years the

Commission gathered both qualitative and quantitative information. They held

public monthly meetings, solicited written input from lawyers, litigants,

experts in the field, court clerks and all interested parties before drafting

the proposal and completing its final work with the recommendations found

here.” --Oregon

Family Law Legal Services Commission

The majority of Oregonians represent themselves in Family

Court. “Oregon data indicates that both sides

are self-represented in approximately 49% of family law filings.”

“Oregonians now represent

themselves in Family Court in 67%-86% of the cases filed. Given the huge

demand for legal help in family law matters that nonprofit law firms

and the private bar cannot meet, access to justice efforts the last 10 years have

concentrated on the statewide availability of model family law forms

and procedural

assistance from courthouse facilitators. Now, budget cutbacks have led to reductions in existing court services

and stalled planning efforts focused on self-representation.” – Executive

Summary. Task Force on Family Law

Self-representation in Family Court is a permanent aspect,

and the legal system’s response “must be actively planned.”

“While the ultimate goal in

access to justice efforts is representation by attorneys, self- representation

is a permanent aspect of the family court. As such, the legal system’s response

to litigants without lawyers must be actively planned.” – Executive Summary.

Task Force on Family Law

Budget pressures and other priorities contribute to reduced

access.

“Since 2007, however,

significant budget reductions precipitated by the poor economy have stalled

energy and funding for both interactive forms and broader self-representation

planning. Moreover, some local courts have eliminated or reduced their

facilitation programs to preserve resources. Simultaneously, the court’s

partners in the access to justice community have continued to struggle with the

high unmet demand for family law legal

services. The poor economy has placed additional stress on this challenge.

In addition, given the enormous public

need for family law help, concern has arisen that market-minded

entrepreneurs may soon preempt access-oriented, quality-focused legal planners

by selling web-based interactive Oregon

family law court forms for profit.” –Executive Summary, Task Force on Family

Law

Most victims of parental, family and organized child

abductions do not have a lawyer at the time of the kidnapping. No Oregon attorney

advertises a practice in child abduction crimes.

There are no “model family law forms” for an abduction. Family law forms require service on the

other party. In abductions, however, the other parties’ and the victim

children’s location is unknown, is likely to be transient, and they may be

living under assumed names.

Abductions are always sneak attacks, with planning and

execution carried out in secret, and nearly always involving multiple

jurisdictions, long distances, more than one perpetrator, and two or more state

legal systems.

Persons participating in a parental, family or organized

kidnapping will likely have intimate knowledge of the victims’ financial

resources, ability to access competent legal assistance and other weaknesses

prior to executing the crime.

There are many variations of legal status. The parents of

the victim children may be married or unmarried, legally separated or not,

divorced or not, with or without custody orders. It may be a grandparent or

some other person who is the primary caregiver for the victim children and

reporting the crime.

A parent whose children have been abducted is likely to be

experiencing severe grief, shock, panic and depression.

HB 2014 will

provide the 2014 Legislative Assembly with critical insights into how to

improve access to justice “when a child is reported to law enforcement

officials as missing by the parent, grandparent or legal custodian of the child”

or is brought to Oregon

under similar circumstances.

III. Finding

legal assistance in the wake of an abduction

Once the victim children have vanished, the victim parent, grandparent

or legal custodian reports the commission of a crime to local law enforcement

and then looks for competent legal advice.

Prior to the passage of Senate Bill 1041 (Aaron’s Law) in

2005, the only avenues of recourse a victim parent (or grandparent) had were

either through the Family Law system or the Criminal Law system. Neither system

recognizes the urgency of the situation, the emotional harm the victims are

suffering, or the fact that the longer the crime continues, the more extensive

and long-lasting the harm.

Neither system provides any point of control for the

victims, who become victims of both the crime and of the system itself.

The Family Law and Criminal Law systems are often

adversarial and have long built-into-the-process timelines, when the issue is

urgent.

Although Senate Bill

1041 (2005) “Aaron’s Law” made Oregon the first state in the nation where

child abduction creates a civil cause of action, no information about the law

or the Parental and Family Abduction Task Force is presently available through

the Oregon State Bar or Oregon State Police web sites.

There is the Yellow Pages and online referral systems, but

neither resource is likely to lead to an attorney specializing in child

abductions.

A. The Oregon State Bar website contains

no information about parental and family abductions. There are no references to

the 2004 Parental and Family Abduction Task Force or Senate Bill 1041 (2005),

Aaron’s Law.

The “search” feature on the OSB website turns up no

information related to Oregon

legislation on the subject.

The OSB Legal Information Topics page contains no

information related to abductions in the Criminal Law or Family Law categories.

There is no link to the Oregon

State Police Missing Children Clearinghouse.

Searches under “personal injury”, “civil suit” and “child

abuse” provide no useful links for abduction victims.

B. The Oregon

Judicial Department website contains no information about parental and

family abductions. There are no references to the 2004 Parental and Family

Abduction Task Force or Senate Bill 1041 (2005), Aaron’s Law.

Among the legal forms available on the website, none are

related to the issue, in which the whereabouts of the abducted children and the

abductors are unknown.

The terms “abduction”, “custodial interference” and

“kidnapping” do not appear in the site’s listing of legal terms and

definitions.

Under the heading “Family Law Topics”, there is no reference

to the crime, and none of the topics link to information about abduction.

There is no link to the Oregon State Police Missing Children Clearinghouse.

C. The Oregon State Police Missing Children

Clearinghouse contains no

references to the 2004 Parental and Family Abduction Task Force or Senate Bill

1041 (2005), Aaron’s Law.

“The mission of the Missing

Children Clearinghouse is to receive and distribute information on missing

children to local law enforcement agencies, school districts, state and federal

agencies, and the public. In 1989, the Oregon

legislature mandated that OSP establish and maintain a missing children

clearinghouse.

“The goal of the Missing

Children Clearinghouse is to streamline the system, serving child victims and

their families by providing assistance to law enforcement agencies and the

public.” – Oregon State Police website

It is rare that a missing or abducted child appears on the

OSP clearinghouse website if a parent is involved in the abduction. The

National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) frequently posts

photographs and other information about parentally abducted on its website that

are not matched on the Oregon State Police website.

As of this writing, NCMEC lists seven Oregon children as parental/family

abductions since 2007, plus Kyron Horman. The OSP site identifies only four of

these children, plus Kyron Horman.

There has been discrepancies of as many as 17 children

abducted from Oregon

who were listed on the NCMEC site but not on the OSP site.

In 2012, the Beaverton Police Department issued a statement

identifying more than a dozen police and governmental agencies who assisted in

the recovery of a child who had been abducted and taken to New Zealand by

his father. The Oregon State Police was not among them, and the child was never

listed as abducted on the Missing Children Clearinghouse website.

IV. The roots of Senate Bill 1041

Aaron’s Law (2005)

A. The 1996 abduction

of Aaron Cruz and his siblings

Aaron Cruz and his three siblings disappeared from Oregon on Feb 12, 1996 despite an

order for joint custody that had been in affect for five years. The number of

adult persons who took, kept and enticed the Cruz children in violation of the

order for joint custody and the Custodial Interference I and II statutes was

greater than ten and included the children’s mother, other family members, and

members of their church congregation that were unrelated to the victims. Their

motivation was to enforce a shunning against the children’s father. The intent

of the shunning was to prevent any contact of any kind between the children and

their father or members of their father’s family, permanently. The shunning

remains in effect today.

The four Cruz children were kept incommunicado and taken to

a series of secret locations in Utah,

where they were pressured to choose between parents, one to love with all their

hearts, and one to despise with equal fervor. Mail sent to my children at their

mother’s last known address in Hillsboro

was forwarded to the address of a conspiring church member in Hillsboro instead of on to the children.

Abducted children are forced to adhere to whatever cover

story their abductors require, are not permitted to grieve their losses, and

are likely to lose access to health care during their time on the run.

Abductors, acting in their own interest, will work hard to sever all emotional

ties the abducted children have to the victim parent.

My children were taken on a journey through three divorces

and three stepdads in three states. My fight to locate and recover my children

would take me through four jurisdictions in three states, usually pro se, but never with the assistance of

an attorney competent in the issue of criminal child abductions.

With a single exception, every court officer, judge,

attorney, juror, witness and police officer I encountered through these four

jurisdictions was white, as were all of the persons participating in the

abduction, and several among them shared membership in the same church

congregation enforcing the shunning.

Although the order for joint custody stated that all

decisions regarding the children’s education and non-emergency medical care

would be made “By Both Parents Together”, I was only able to access two

after-the-fact medical reports

for Aaron from Utah,

and none for my other three children after they disappeared from Oregon in 1996.

Prior to his abduction from Oregon, Aaron had no history of any serious

illness or injury. The first medical report for Aaron was an intake report

dated a year after his abduction began. He had been hospitalized for expressing

suicidal ideation. The report described him as severely depressed, underweight,

and noted many long scars from self-inflicted knife wounds across both of his

upper arms. The report quoted him as saying he cut himself to relieve his

emotional pain.

The second medical report I received from Utah about Aaron was his death certificate,

which stated that he had died from “undetermined causes.” He may have been a

suicide—there was a note—but it is also likely that he had run out of his

anti-seizure meds, suffered a seizure, fell into a coma and died.

When my three living children and I gathered around Aaron in

the Intensive Care Unit in Payson,

Utah, in April 2005, where he lay

comatose, it was the first time the five of us were together since the

abduction/shunning began in 1996.

Over the course of several days, from arriving at the

hospital to Aaron’s funeral service, my three surviving children and I spent

many hours together, and it appeared that we would re-establish our

relationships going forward.

My son Tyler, a member of the Utah Army National Guard,

invited me to see him off on his second tour to Iraq several weeks after Aaron’s

death, and we spent five days together at Camp

Shelby, Mississippi.

Tyler called me from Kuwait and sent me a single email from Ramadi, and we

appeared to be well connected, but over the next few weeks all of my children’s

email addresses and phone numbers went dead, just like every other time I found

them since the abduction began.

The shunning remains in effect today. Neither the Family Law

or Criminal Law systems in any of four jurisdictions in three states looked at

the persons engaged in the abduction, other than my former wife. After filing

the initial police report, I was never interviewed by a police detective.

B. Legislative

history of Aaron’s Law

1. Reporting the

crime to the Legislative Assembly: During the 2001 legislative session, I met with Senator Avel Gordly in her

office in the Capitol and described the abduction of my children and the

failures of both the Family Law and Criminal Law systems to protect my family.

She promised to work on the issue.

In the fall of 2002,

Senator Gordly offered me the opportunity to serve as her legislative staff in

the upcoming 2003 session.

In the 2003

session, I testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee and the Joint Ways and

Means Public Safety Subcommittee. Senate President Peter Courtney appointed the

Senate President’s Interim Task Force on Parental and Family Abductions,

co-chaired by Senator Gordly and Senator Frank Morse.

The 2004 Task

Force on Parental and Family Abductions was intended to build on the prior work

of the Family Law Task Force, which had been co-chaired by William Howe III and the Honorable Judge Maureen McKnight, and

Judge McKnight was among those appointed to the abduction panel. I testified

before the Task Force in 2004.

The Family Law Task Force had worked on strategies to reduce

the incidence of divorce in Oregon,

including the requirement that both parties enter into counseling before a

divorce is granted, in the event that some parties might reconsider for the

sake of the children. This idea would be incorporated into Senate Bill 1041 in

2005.

During the 2005

legislative session, I testified on the crime and in support of Senate Bill

1041 before the Senate Judiciary Committee, the Senate Rules Committee, and the

House State and Federal Affairs Committee.

Senate Bill 1041 passed the House on a unanimous vote and

was signed into law by Governor Ted Kulongoski in 2005.

2. Take Root – Adults

who were abducted as children speak: Take Root is an advocacy group whose

membership is entirely composed of adults who were abducted by their parents

when they were children. Liss Hart-Haviv, the Executive Director and founder of

Take Root, was a key member of the Parental and Family Abduction Task Force.

Statement by Take Root:

“Children who are hidden

from the justice and child protective systems by a fugitive parent are no less ‘missing’

than children taken by non-family members, and may find themselves in just as

much danger.

“50% of Take Root members

who were abducted by parents were also physically or sexually abused by those

parents.

“Almost all suffered

profound psychological trauma from being cut off from their loved ones and kept

‘off the grid’ to evade discovery, sometimes deprived even of medical care or,

more commonly, schooling.

“However, when society

hears about the crime of family abduction it is typically from the perspective

of a left-behind parent expressing his or her anguish over having a missing

child, or a taking parent justifying his or her actions.

“Seldom do we have the

opportunity to hear, firsthand, from the child about the experience of being abducted. Take

Root was established as a platform for the abducted to tell their side of the

story.

“It is our hope that

raising awareness of the true danger and devastation faced by children who are

abducted by individuals to whom they are related will put an end to such cases

being dismissed as “custody battles” between parents.

“Take Root’s uniquely child-centered

training workshops and resources have proven effective at changing perceptions

of family abduction; educating law enforcement, policy makers, child advocates,

and missing child case managers from coast to coast about the realities of this

devastating crime against children.”

“Nothing can replace the personal and professional experience that Take

Root’s workshops present, the focus on the child as victim – which can

sometimes get lost in the legal and technical aspects of the case or day-to-day

dealings with parents. Liss Haviv’s presentation was truly an incredible

experience and scored a perfect “5” on the evaluations – a first since we began

the class.”- Ellen Conway, Director, Office of Children’s Issues, US

Department of State

3. The Task Force on

Parental and Family Abductions (2004)

The Task Force held a series of meetings, took expert

testimony, and produced a Final Report to the Senate President prior to the

2005 legislative session.

Among the Task Force’s

key findings were:

a. No numbers:

that no person or entity knew the number of Oregon children suffering parental and

family abductions in any given period of time. No one tracks the cases on a

statewide basis. A parent’s report of the abduction of their child likely went

no further than the City or the County taking the police report. This is

probably still the case.

b. A broad lack of

awareness: That there was a general lack of awareness among law

enforcement, the courts, the bar and social service professionals, which

partially explains the low priority all give to non-stranger abduction cases.

This lack of awareness factors into the system’s willingness to allow the

abducting parent and the parent’s associates to keep the children indefinitely,

and the failure of law enforcement, the bar and court officers to understand

that abductions are crimes in progress and respond accordingly.

c. Some parents use

their children as weapons: That “often” parents “often” take out their

anger with each other through their children, and that some “even abduct their

own child.” The Task Force found “that this is extremely detrimental to the

emotional and mental well being of the children, and at time may even put the

life of the child in danger.” Non-parental accomplices of these crimes are even

more likely to disregard the safety and wellbeing of the abducted child.

d. Long-lasting

trauma, injury and damage: The real injuries an abducted child suffers is

not recognized in current statute. “…the injury a child receives, when the

child has been abducted by one of the child’s parents, does not necessarily

include physical injury. The injury is

more in the nature of mental trauma or mental injury. Nonetheless, the injury

is real and may be even more long lasting and damaging than physical injury.”—Abduction

Task Force

e. Damage similar to

sex crimes against the child: The Task Force recommended that the 2005

Legislative Assembly increase the statute of limitations for Custodial Interference

I and II offenses:

“This would mean that the statute of limitations for

custodial interference would be the same as it is currently for sex offenses.

Your Task Force believes that the rationale for doing this is the same for the

statute of limitations on sex crimes. A child who is removed from the lawful

custody of one parent by another is a victim. That child is similarly situated

to many underage victims of sex crimes. The perpetrator of the crime is the

child’s parent. Too often, at the time of the offense, the victim is unaware

that they have been abused or that they have a right to seek redress. LC 847

would give a person, who as a child was a victim of a

parental abduction, the ability to seek prosecution when the

person is an adult and better able to understand the ramifications of the

abduction.” –from the Final Report

While the 2005 Legislative Assembly did not follow the Task

Force’s recommendation on extending the statute of limitations, Senate Bill

1041 did address the issue, providing child victims with a window to hold the

child’s abductors accountable that extends to six years after the child has

attained the age of 18.

4. “Burning Issues in Access to Justice”

The 4th Family Law Conference, titled “Out of the Frying Pan: Burning Issues in

Access to Justice”, sponsored by the Oregon Judicial Department and the

State Family Law Advisory Committee, was held in Bend, Oregon, April 7-8, 2006.

Workshop #6: Encountering Family Abductions in the Legal Setting.

This workshop will offer information about family abductions, including

international abductions and the Hague convention, prosecution of custodial

interference, and

statutory approaches to preventing and dealing with abduction cases including

the new Aaron’s Law (SB 1041, Ch 841, Oregon Laws 2005). Dr. Edward

Vien, Psychologist, Portland;

Hon. Terry Leggert, Circuit Court Judge, Marion County; Liss Hart-Haviv,

Executive Director, “Take Root”; Kathy Root, Attorney at Law, Portland;

Marshall Spector, Attorney at Law, Portland.

5. Aaron's Law in statute:

ORS 30.868

30.868

Civil damages for custodial interference; attorney fees. (1) Any of the following

persons may bring a civil action to secure damages against any and all persons

whose actions are unlawful under ORS 163.257 (1)(a):

(a)

A person who is 18 years of age or older and who has been taken, enticed or

kept in violation of ORS 163.257 (1)(a); or

(b)

A person whose custodial rights have been interfered with if, by reason of the

interference:

(A)

The person has reasonably and in good faith reported a person missing to any

city, county or state police agency; or

(B)

A defendant in the action has been charged with a violation of ORS 163.257

(1)(a).

(2)

An entry of judgment or a certified copy of a judgment against the defendant

for a violation of ORS 163.257 (1)(a) is prima facie evidence of liability if

the plaintiff was injured by the defendant’s unlawful action under the

conviction.

(3)(a)

For purposes of this section, a public or private entity that provides

counseling and shelter services to victims of domestic violence is not

considered to have violated ORS 163.257 (1)(a) if the entity provides

counseling or shelter services to a person who violates ORS 163.257 (1)(a).

(b)

As used in this subsection, “victim of domestic violence” means an individual

against whom domestic violence, as defined in ORS 135.230, 181.610 or 411.117,

has been committed.

(4)

Bringing an action under this section does not prevent the prosecution of any

criminal action under ORS 163.257.

(5)

A person bringing an action under this section must establish by a

preponderance of the evidence that a violation of ORS 163.257 (1)(a) has

occurred.

(6)

It is an affirmative defense to civil liability for an action under this

section that the defendant reasonably and in good faith believed that the

defendant’s violation of ORS 163.257 (1)(a) was necessary to preserve the

physical safety of:

(a)

The defendant;

(b)

The person who was taken, enticed or kept in violation of ORS 163.257 (1)(a);

or

(c)

The parent or guardian of the person who was taken, enticed or kept in

violation of ORS 163.257 (1)(a).

(7)(a)

If the person taken, enticed or kept in violation of ORS 163.257 (1)(a) is

under 18 years of age at the time an action is brought under this section, the

court may:

(A)

Appoint an attorney who is licensed to practice law in Oregon to act as guardian ad litem for the

person; and

(B)

Appoint one of the following persons to provide counseling services to the

person:

(i)

A psychiatrist.

(ii)

A psychologist licensed under ORS 675.010 to 675.150.

(iii)

A clinical social worker licensed under ORS 675.530.

(iv)

A professional counselor or marriage and family therapist licensed under ORS

675.715.

(b)

The court may assess against the parties all costs of the attorney or person

providing counseling services appointed under this subsection.

(8)

If an action is brought under this section by a person described under

subsection (1)(b) of this section and a party shows good cause that it is

appropriate to do so, the court may order the parties to obtain counseling

directed toward educating the parties on the impact that the parties’ conflict

has on the person taken, enticed or kept in violation of ORS 163.257 (1)(a).

The court may assess against the parties all costs of obtaining counseling

ordered under this subsection.

(9)

Upon prevailing in an action under this section, the plaintiff may recover:

(a)

Special and general damages, including damages for emotional distress; and

(b)

Punitive damages.

(10)

The court may award reasonable attorney fees to the prevailing party in an

action under this section.

(11)(a)

Notwithstanding ORS 12.110, 12.115, 12.117 or 12.160, an action under this

section must be commenced within six years after the violation of ORS 163.257

(1)(a). An action under this section accruing while the person who is entitled

to bring the action is under 18 years of age must be commenced not more than

six years after that person attains 18 years of age.

(b)

The period of limitation does not run during any time when the person taken,

enticed or kept in violation of ORS 163.257 (1)(a) is removed from this state

as a result of the defendant’s actions in violation of ORS 163.257 (1)(a).

[2005 c.841 §1; 2009 c.11 §5; 2009 c.442 §26]

V. The principles of Aaron’s Law

Child abduction,

causing a child to disappear for any length of time, is child abuse. The

consequences can be devastating to the child and the child’s family, with

damages accruing minute by minute over months and years. The harm can extend

into the next generation. Much of the damage can never be remedied. Deterrence

and prevention is vital. Custodial interference statutes are ineffective. The

Criminal Law and Family Law systems do not provide an appropriate response to

the problem. Victims ought to be able to hold their children’s abductors

accountable in civil court. Child victims ought to be able to hold their

abductors accountable in civil court once the child has become an adult. No

person is exempt from the law.

A. Victims in

control, not the system: The Civil Suit

You are the parent of a child abducted by the other parent.

You did not see this coming. You do not know where they are, where they are

going, if they are using assumed names or many other important details. Your

child may have medical issues. You are certain that your ex intends to keep

your child from you permanently.

Now you have to convince someone—many persons in a gulag of

systems and strangers—that you are not exaggerating, that your child is

suffering, that this is an emergency. You must find legal help in at least two

state systems.

Having reported the crime to law enforcement and facing the

systemic access to justice and lack of awareness issues outlined above, the

victim parent, grandparent or legal custodian either enters the Family Law

system pro se, or finds an attorney

willing to take the case. Family Law attorneys will tell you that they do not

practice criminal law. They will work the case as a custody issue.

The Family Law system is a labyrinth of overburdened courts,

bewildering forms and procedures, long timelines, requirements that make swift

action impossible, and staffed by persons who lack awareness of the difference

between a custody fight and a cold-blooded kidnapping.

Law enforcement response to the abduction is subject to

statutory issues identified elsewhere in this report, and the fact that no

charges will be filed before

prosecutors believe that they have sufficient evidence to

convince a jury to reach a unanimous verdict “beyond a reasonable doubt.” The

Kyron Horman abduction, now entering its third year, illustrates this point

very clearly.

The Criminal Law system is also very rigid in certain

respects, and the victim parent may not want to see the abducting parent go to

jail, as was the case in the Cruz abduction. . In many

cases, incarcerating a parent adds to the ongoing trauma suffered by the child

victims.

Neither system offers good, appropriate choices for the

victim family.

Filing a civil suit for damages against persons who you can locate,

however, who you can prove “by a preponderance of the evidence” instead of

“beyond a reasonable doubt” did in fact “take, keep or entice” your child in

the course of the abduction, provides abduction victims with a range of options

unavailable in either the criminal or family law systems.

Civil suits can be brought forward more quickly also,

potentially shortening the time that your child is abducted, and time is of the

essence in kidnappings.

With the passage of

Senate Bill 1041 in 2005, Oregon became the first state in the nation where

abducting a child creates a civil cause of action, the right to sue for damages

to your child and your family, and the right of the abducted child to seek

redress when the child becomes an adult.

B. Who you serve and 142

reasons why:

You probably do not know where your ex is concealing your

child and thus cannot serve legal process papers, but you become aware that

your ex has assistance in carrying out the crime, whether providing logistical,

financial or planning support in taking, keeping or enticing the child.

This person or these persons can likely provide information

leading to where your child is being concealed. You file suit under ORS 30.868, Aaron’s Law.

Aaron’s Law is intended to serve as a powerful deterrent to

persons considering aiding in a parental, family or organized child abduction.

The prospect of defending oneself against liability for “(a) Special and general damages,

including damages for emotional distress; and (b) Punitive damages”, as

well as attorney’s fees, would discourage many from joining in facilitating a

kidnapping.

The

Kyron Horman abduction illustrates the concept very plainly.

The disappearance

of 8-year old Kyron Horman nearly three years ago triggered the largest search

effort in Oregon

history. No criminal charges have been filed in the case, and police have

released an age-progressed image of what they think Kyron might look like

today.

Last seen in the

company of his step mom, Terri Horman, the multiple searches turned up no trace

of the child. Law enforcement has named no suspects or persons of interest, officially, although those terms most

certainly describe Kyron’s step mom Terri Horman and her close friend DeDe

Spicher, unofficially.

Both women have

stubbornly refused to account for their whereabouts during the crucial two

hours on the morning of June

4, 2010, when Kyron vanished from the face of the earth, as did

these two women, albeit temporarily in their cases.

With both the

criminal and family law courts at a stand still, unable to move forward,

Kyron’s mother Desiree Young filed a civil suit against Terri Horman, alleging

that the step mom knows where Kyron is and whether he is dead or alive.

DeDe Spicher invoked the 5th

Amendment 142 times during her deposition.

C. Domestic violence

exception:

No “public or private entity that provides counseling and shelter services to victims of

domestic violence” can be sued under Aaron’s Law, nor can parents fleeing

domestic violence situations.

D. Counseling for

resolution and deterrence:

Borrowing from the Abduction Task Force’s predecessor, the

Family Law Task Force, Aaron’s Law authorizes the Court to order “the parties”

to the civil suit into counseling directed at educating “the parties” as to the

harm their conduct is causing the victim children.

This feature is intended to serve as a tool for both

resolution and deterrence.

E. The child victim

becomes an adult:

The Parental and Family Abduction Task Force noted the

similar trauma in child abduction and child sex crime victims, recommending an

increase in the statute of limitations, but no change to the criminal statute has

been made. Under Aaron’s Law, however, a child victim has a six-year window to

hold persons participating in the abduction accountable, beginning when the

child becomes an adult.

This concept is intended to serve in the cause of justice

and as an additional deterrent. It also better places the Custodial

Interference I and II statutes in the context of the crime, which is a continuing crime, and the persons

involved are responsible for everything that happens after the kidnapping is

initiated.

F. Protecting the

interest of the child:

When a civil suit is filed under Aaron’s Law, the Court is

immediately authorized (encouraged) to appoint legal and mental health and

other qualified professionals to see to the interests of the child, and to

assess the costs to “the parties” as the Court sees appropriate.

This concept results in part from the findings of the

Parental and Family Abduction Task Force. The cost assessment feature is

intended to act as a further deterrent.

G. Aaron’s Law and

child trafficking:

While ORS 30.868 Aaron’s Law has yet to be tested in a child

sex trafficking case, it could be a very useful tool in providing resolution

and as a deterrent, were it to be better understood by professionals working in

that field.

VI. Case Study: The Kyron Horman

abduction

“There is no case like this.”

A. “There is no case

like this.”

The Kyron Horman abduction is unique in many respects. The

missing child has triggered the largest search effort in the history of Oregon, now entering its

third year.

It is also the first known instance of a filing under ORS

30.868 Aaron’s Law.

Desiree Young, Kyron’s mother, filed the civil suit on June 1, 2012, as reported in

The Oregonian:

“There is no case

like this – even close to these circumstances,” (Multnomah Judge Henry) Kantor

said….

…."I will forever have a

hole in my heart because he is not here," Young said, shaking as she stood

outside Portland's Justice Center and beside respected civil rights attorney

Elden Rosenthal.

….The lawsuit argues that Terri Horman

"intentionally interfered" with Young's parental rights, and

intentionally inflicted severe emotional distress on her. Young shared joint

legal custody of Kyron after her divorce from Kaine Horman in 2003.

Rosenthal pledged to aggressively use all the

tools afforded to him in a civil case "to peel away the layers of mystery

surrounding Kyron's disappearance," and to add more names to the suit if

others are responsible. He said he will issue subpoenas for witnesses to

testify under oath, and compel the production of documents, such as e-mails and

text messages.

"There

are some cases that require victims of wrongs to use the civil justice

system," Rosenthal said. "This case is one of them."

Kyron Horman’s is the only Oregon abduction case that has lasted longer

in the media than a single news cycle. Most parental and family abduction cases

never make the news. The families suffer in private, and an abduction case is

isolating by its very nature.

Kyron’s disappearance attracted media attention for three

reasons unique to the case:

1. He disappeared from his school, attracting attention from

parents, teachers and school officials across the state and beyond. Most

kidnappers will want to avoid attracting attention.

2. No one else close to Kyron was also missing.

3. Kyron’s stepfather is a police detective. When he was

discovered missing, his family had instant credibility with law enforcement,

and police were on it in a matter of minutes.

B. On meeting “The

Criteria”:

The Kyron Horman abduction is complicated for many reasons.

Obviously, law enforcement has not been able to assemble evidence sufficient to

move a jury to a unanimous verdict “beyond all reasonable doubt”, which is why

no criminal charges have been filed.

This obstacle in the Criminal Law system is holding back

both the Family Law process and the civil suit filed under Aaron’s Law.

But most parental and

family abductions do not face this obstacle, because there is no criminal

proceeding under way and law enforcement is not actively looking for the

abducted child(ren).

During a press conference two years ago, the Multnomah

County Sheriff was asked if there were any other missing children besides Kyron

out there, and the Sheriff responded “none that meet the criteria.”

Whatever “the criteria” is, it is important that both the

public and the professionals whom the public relies on for justice and to

protect their families understand what the criteria is, what the rules are and

how to make them work better.

HB 2014 will

provide the 2014 Legislative Assembly with information vital to making the

Criminal Law, Family Law and Civil Law systems work better for the benefit of

all Oregon

children, and for those children who are brought to Oregon under similar circumstances.

VII.

Attitudes as Obstacles to Access to Justice

“Happy

families are all alike; every unhappy family is

unhappy in its own way.” –Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

My personal experience as the parent of abducted children is

my own, but over the years since I began working on child abduction prevention

legislation, several dozen Oregon

parents whose children have disappeared with the ex (and the ex’s associates)

have contacted me.

In the details of their respective family situations, they

each had their own stories. Some were still married to the other parent; some

had never been married; some were in the process of divorce; some long

divorced. Their legal status was of every sort, and the number and ages of the

victim children as varied as can be.

But in the issue of access to justice, all of the stories

were the same, the same as mine, we parents of children abducted by known

perpetrators.

These grieving parents had all reported the crime to law

enforcement, but the police were not looking for their children. They were all

in some sort of limbo—at best—with the Family Law system. Some had lawyers at

different points in their story, some did not. They all reported problems in

finding a lawyer willing to listen, much less help, and all while time slipped

away forever.

A father whose non-custodial ex-wife had disappeared with

the children in February was told by a police detective the following September

that the department couldn’t act because the Custodial Interference statute had

no definition of “protracted.” They couldn’t be sure it had reached that point.

The children were eventually recovered from Arizona.

These parents had found me through my writing posted on the

web. They had gone online desperate for help, for ideas. They had learned about

Aaron’s Law and had read it through, but were unable to find a lawyer in Oregon who was familiar

with ORS 30.868.

This is why they were contacting me, after all of this had

happened. And there was yet a missing child and time was of the essence, and

they were clinging to threads of hope.

“Your children will

find you some day (Don’t worry be happy)”

In my experience, supported in conversations with these

other parents of children abducted by known perpetrators, significant barriers

to recovery and in access to justice lie in people’s minds, both in those who

people The System and those in the general public, all stemming from the same

lack of awareness.

Moving a child during the course of a custody battle is one

thing; causing the child to vanish is

another. Taking, keeping or enticing a disappeared child that a person is

not related to ought to be a behavior that the System especially discourages,

and sharply. A person aiding and abetting the taking of that disappeared child

across state lines ought to be held accountable.

But there is a tendency for people to marginalize the crime,

if not exactly trivialize it. Be patient.

It will be OK. People with passive personalities will counsel more patience

and an optimistic attitude. Your children

will find you some day. Writing off your child’s entire childhood…learn to accept it…your teenager’s

entire adolescence…Keep your chin up,

someday your grandchild will want to know something about you…People wonder

when you will move on.

Caseworkers have big caseloads; department budgets are

constrained; No one knows what “protracted” means; most Oregonians cannot

afford an attorney….

We ought to know,

however, what chain of events takes place when a child disappears, either from Oregon or into Oregon. Please move HB 2014 forward.