By Sean Cruz

Portland, Oregon—

I arrived in Fairfield California on Monday planning first to visit my parents’ and grandparents’ gravesites and then look up some old friends, but my itinerary changed as soon as I arrived at the cemetery and saw the condition of the graves.

A pile of green glass shards, the remains of a broken vase left by one of her friends, lay beside my grandmother’s tombstone, needed immediate attention, and as I reached down to collect the pieces one of them bit me hard on the end of the finger, cut me so deeply it was still bleeding the next day.

“Ow!” I said. “Lo siento mucho, grandma. I am sorry.” Thus began a daylong conversation with my ancestors.

“Where have you been, mijo? What took you so long?” she said, silently but directly, pointedly.

“I am sorry, grandma. I love you.”

I know she was glad I had come, had returned home.

The Cruz family plots are located on a hillside in the old section of the cemetery, where the dense, irregular clusters of upright monuments and above ground tombs make upkeep difficult and more time consuming for the maintenance crews. There’s an Old California feel to the place, many of the names Spanish first and last, and there are many old shade trees scattered throughout and houses in the surrounding neighborhoods with red terra cotta tile roofs.

Blood on my clothes, on the side of the car, gushing out of my finger, sopping up the blood with paper towels, I cleared the graves where my grandparents lay side by side, where my parents lay side by side, where my beloved uncle Victor lay, he of the movie star good looks, idolized by all of us children, whose tire caught a patch of gravel in the valley one summer night in 1960, spun him out of control to an early death at the age of 26.

I had returned to Fairfield only twice in the last ten years.

Ten years ago we laid my mom to rest here beside my dad, who had preceded her by twenty-five years.

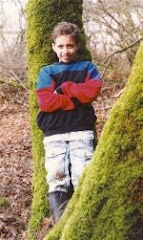

I came here for a funeral visit five years ago also, the day after we buried my son Aaron in El Dorado Hills, north of Sacramento. At the time of his death, I had refused to argue with my former wife over where Aaron would be buried, and she had chosen a place convenient for her and stepdad number three, who had never known my son, a story for another day.

This is an ancestor story, an elders story, a generations story, a story of gratitude, of paying respect, not the story of a young man lying alone on a hillside among strangers, a son as abducted in death as he was kidnapped in life.

I will get to that story in a few days.

The headstones all faced east into the warm morning sun. The ground was baked hard, the crab grass tough and difficult to dig out. I worked with the one tool that I happened to have with me, a folding shovel with a 12-inch handle.

I was aware that I could call any one of several friends and borrow landscaping tools, and a maintenance truck festooned with real shovels and other equipment was parked no more than fifty feet away, but I elected to work with what I had brought with me.

My ill-preparation was part of my conversation with my folks, particularly with my Dad.

“If you had thought this through, son, there wouldn’t be a problem with the tools.”

“Yes. You’re right, Dad. Next time, I will come prepared.”

The ground was so hard that the shovel was mostly useless as a digging tool. I adjusted the handle to use it as a hoe to chop at the edges, and I thought about that, too.

A hoe with the short handle. El cortito. The short one. Short hoes similar to this one had ruined the backs of countless millions of mostly-Mexican farmworkers before Cesar Chavez organized the effort that resulted in its ban, and I was reminded of how hard that labor was, down on my hands and knees as the sun rose on my back.

A couple of hours into the work, the hard ground separated the blade from the handle and I finished edging the sites chopping with the blade only, held between my two hands.

Tools hung in racks on the maintenance truck nearby, and friends were only a phone call away, but there was a certain amount of penance to be paid this day, and devices that would ease the work or shorten the time would interfere with the process and intrude on my silent conversations.

I broke for lunch, drove to meet old, old family friend Chuck Johnson for cheeseburgers and reminiscence. I had brought with me a Christmas card that his parents had sent to mine decades ago, with it a photograph of the Johnson family on it, and I had wanted to return it to them, this too in the spirit of paying respect to our elders.

I returned to the cemetery with bags of topsoil and live flowers to plant in the ground.

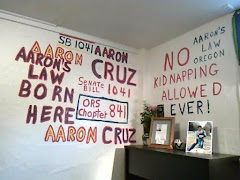

I had brought glass vases from Portland and fresh flowers cut from my friend Michael Iverson’s Sacramento yard for the graves, and I had brought a rock from the Columbia River, a chunk of basalt with my son’s name and yellow flowers painted on it to place with my parents, the grandson whose name now references Oregon’s Aaron’s Law, the only law in the nation whereby persons who abduct children can be held accountable for the damage they cause in the lives of innocents.

I’ll have more to say about that, too. With this trip to Sacramento, I began the work to see Aaron’s Law take effect in California. I brought several Columbia River rocks with Aaron Cruz’s name painted on them, and I place the rocks where I plant the seed of the Law.

As I molded the new soil with my hands, planted and watered the new flowers, completed my conversations with the folks, with grandma and grandpa and Uncle Victor, I was aware that this day marked a new beginning for me.

I will be back. Soon. Often. There is a foundation to build on here.

Family. Generations. Ancestors. Past…and the future.

My parent's headstone reads: "Sunshine, fresh flowers, green grass. Together at last."

That California sun spoke to me. I drove on those California roads and highways with the windows rolled down, just like in the old days, just like home.