By Sean Cruz

Portland, Oregon—

My grandparents lived at the edge of town, in a wood frame house in the Sacramento valley that they had surrounded with flower and vegetable gardens, trellises, grape vines and cactuses that thrived in the California sun, a chicken coop in the back, where the rooster roamed.

They had planted fruit trees, apricot, peach, plum, walnut, almond, fig and olive, long before I was born and they all easily bore my weight and that of my brother, our cousins and friends, significant chunks of childhood spent up in those trees or throwing figs at each other, racing around the house and barn or into the fields across the street. I never acquired a taste for figs, but they made superb missiles, much better than the other fruits and vegetables near at hand, and the seasonal fig fights began as soon as they were large enough to throw, still green on the tree.

My grandparents grew corn, grapes, tomatoes, peppers and chilies, cucumbers, squash, beans and peas, all destined for the kitchen table, where my grandmother made fresh tortillas every morning, where a pot of beans was always steaming on the stove, never so warm as the love she gave us children, memories of my grandmother and her red and white checked tablecloth….

My father also kept a vegetable garden in our backyard, where he spent many an hour working his stress into the earth, a facet I did not understand until later, after he was gone, and I had become an adult working in my own garden, the soil absorbing my own stress, clearing my mind, building a life for my own young family, tomato plant by tomato plant.

My father suffered a series of heart attacks, two of them while working in his garden amid the corn stalks and jalapenos. There were tears in his eyes when he told me that he would no longer be able to work out there, his heart going bad in those days before bypass surgery was available, the technology that would have saved his life not quite invented yet, and he was gone in 1975 at a youthful 52 years of age, far too soon.

My grandmother passed in 1980 at the age of 80, at least 50 of those years spent in that house, in that kitchen, in the gardens. After the house was sold, the new owners allowed the property to sink into neglect, and within a couple of years the entire garden was dead, most of the trees cut down, a tragedy, an affront, a paradise lost.

When I work in my own garden, I think of my father and my grandmother mostly. I think about the life they built for me, the foundations they laid, the garden paths they designed. I understand how valuable gardening time was to my father, and I know that I honor him when I work out there. I speak to my father in my garden.

In the eight years that I have lived here in this house, I have put hundreds of plants into the ground, all with thoughts of my parents, my grandparents and my children, all with reflections on the past, the present, the future. Plants, you see, are often not just plants….

I put fruit trees into the earth, cherry, peach and apricot, in part to connect me to those California gardens I grew up in, but the climate in Portland does not favor these varieties, and after having only one good crop, I’ve taken out the peach and apricot. I'll replace the cherries this spring.

I planted an olive tree a few years ago. It’s about eight feet tall now, and I’m going to learn how to cure the olives pretty soon.

I have a remnant of my grandmother's garden, an old concrete birdbath on a pedestal, a frog figure on top, that part broken decades ago, standing in an honored place under my olive tree, shaded, protected, priceless....

I’ve planted strawberries, blueberries, cactus, bamboo, sage, all the common garden vegetables, potatoes to tomatoes, and built a greenhouse from recycled glass doors and windows and assorted found objects, painted up in many bright colors, a couple of murals on the fence.

I like to think that after I am gone, the garden will endure, will live on, that someone will work it, knowing the linkage and the history, that the connection between this garden and my father’s garden and my grandmother’s garden will be unbroken, a legacy of fruit and vegetables and the earth to be sure, but most importantly a legacy of love, of intergenerational love, born in a grandmother’s heart, and shared on a red and white checkered tablecloth.

Before my four children disappeared in 1996 in a Mormon kidnapping, I used to work my garden with my children, like my father before me.

My grandparents names were Victor and Dominga Cruz; my parents names were John and Olive Cruz; my children’s names Natalia, Aaron, Tyler, Allie…. Honor to you, love always….

I tend a garden of intergenerational love. Sometimes it tastes like cucumbers, sometimes like snow peas, today it tastes like unfrozen strawberries, Oregon strawberries from the east side of the house….

It always tastes of love….

Friday, December 31, 2010

In the Garden of Intergenerational Love (for W)

child abduction,kidnapping,parental abductions

Aaron Cruz,

Allie Cruz,

mormon abduction,

Natalia Cruz,

Tyler Cruz

Monday, December 6, 2010

The last days of Aaron Cruz: Interlude 1: Quality Time

By Sean Cruz

Portland, Oregon—

Anyone with a large family would know how difficult it is to have quality time alone with each of your children separately, times when it is just the two of you and the time and experience together is genuinely “quality” time for everyone.

As a divorced single parent with two boys and two girls and an order for joint custody, time with my children was always at a premium, and how to satisfy each of their differing interests, wants and needs simultaneously always a balancing act as the months and years went by.

Aaron created a way for him and me to share some regular quality time together, and he made it happen on his own initiative during the year before he and my other children disappeared into Utah.

During the school year, the joint custody order stated that the children would reside with me immediately after school on Fridays and through the weekends at varying lengths.

Every Friday, after picking up my children, we would stop at a grocery store on the way home, so each of the kids could have input into what foods we would have for meals and snacks during our time together. The kids and I would negotiate our preferences as we walked through the store so that everyone left happy about something.

This is how grocery shopping became part of our quality time together as a family, except for my mom, who was housebound from her chronic illnesses. I was my mother’s sole caregiver in those days.

Aaron hungered for something more than food, however. He hungered for more time with me, just the two of us, and he developed a plan to carve that time out every Friday. I was skeptical at first, but he worked his plan to perfection.

He found out what each of his sisters and his brother wanted from the store, and he asked them for backups if their first choices weren’t available. Aaron put a lot of effort into his interviews with his siblings, because he wanted to eliminate each of their desires to go shopping with us, this week and every week.

These could be very complex arrangements, fascinating to listen to their negotiations, how they planned their snacks, with much bartering and swapping and sharing after the grocery run.

Under his system, Aaron and I would drop the other kids at home with my mother, where Natalia and Tyler would generally make a beeline for the video games and Allie would play with my mom’s dachshund Sox, and all of the kids together would provide love and companionship for their grandmother, and he and I would make our grocery run for my family, for our family. Everyone was content at the very same time.

Our last grocery run together was Saturday, February 10, 1996. Aaron, Natalia, Tyler and Allie disappeared two days later, on their way to the home of Mormon zealots Chris and Kory Wright in a remote area in the mountains east of Ogden, Utah, I would later learn. This was the first place that my children were concealed.

I think about Aaron every time I set foot in a grocery store, ever since those days we were together as a family.

I miss his companionship and how he would explain to me in exquisite detail what item was for which child as he placed things into our shopping cart.

I could enjoy this time with Aaron free of anxiety for the other kids and for my mom, because they were home together and they were all safe. I would hold off shopping for myself until Fridays, so I could go with Aaron. I also hungered for that time.

Aaron would distribute the snacks and treats to the other kids when we got back to the house, and there was never a disappointed word.

All was good under the sun, dependably good, every Friday afternoon, without fail. I still have the grocery receipts.

When I recovered Aaron from the abduction in 2003, he was too ill to go shopping, and then he was ordered to return to Utah for deployment to Iraq, and then he became more ill there in Payson, and then came his Last Days.

To this day, I never enter a grocery store without thinking of Aaron, without feeling his absence, without remembering that last day that my family was safe, together and at home.

And then the Mormons entered the picture, and with them an abduction and a program….

Portland, Oregon—

Anyone with a large family would know how difficult it is to have quality time alone with each of your children separately, times when it is just the two of you and the time and experience together is genuinely “quality” time for everyone.

As a divorced single parent with two boys and two girls and an order for joint custody, time with my children was always at a premium, and how to satisfy each of their differing interests, wants and needs simultaneously always a balancing act as the months and years went by.

Aaron created a way for him and me to share some regular quality time together, and he made it happen on his own initiative during the year before he and my other children disappeared into Utah.

During the school year, the joint custody order stated that the children would reside with me immediately after school on Fridays and through the weekends at varying lengths.

Every Friday, after picking up my children, we would stop at a grocery store on the way home, so each of the kids could have input into what foods we would have for meals and snacks during our time together. The kids and I would negotiate our preferences as we walked through the store so that everyone left happy about something.

This is how grocery shopping became part of our quality time together as a family, except for my mom, who was housebound from her chronic illnesses. I was my mother’s sole caregiver in those days.

Aaron hungered for something more than food, however. He hungered for more time with me, just the two of us, and he developed a plan to carve that time out every Friday. I was skeptical at first, but he worked his plan to perfection.

He found out what each of his sisters and his brother wanted from the store, and he asked them for backups if their first choices weren’t available. Aaron put a lot of effort into his interviews with his siblings, because he wanted to eliminate each of their desires to go shopping with us, this week and every week.

These could be very complex arrangements, fascinating to listen to their negotiations, how they planned their snacks, with much bartering and swapping and sharing after the grocery run.

Under his system, Aaron and I would drop the other kids at home with my mother, where Natalia and Tyler would generally make a beeline for the video games and Allie would play with my mom’s dachshund Sox, and all of the kids together would provide love and companionship for their grandmother, and he and I would make our grocery run for my family, for our family. Everyone was content at the very same time.

Our last grocery run together was Saturday, February 10, 1996. Aaron, Natalia, Tyler and Allie disappeared two days later, on their way to the home of Mormon zealots Chris and Kory Wright in a remote area in the mountains east of Ogden, Utah, I would later learn. This was the first place that my children were concealed.

I think about Aaron every time I set foot in a grocery store, ever since those days we were together as a family.

I miss his companionship and how he would explain to me in exquisite detail what item was for which child as he placed things into our shopping cart.

I could enjoy this time with Aaron free of anxiety for the other kids and for my mom, because they were home together and they were all safe. I would hold off shopping for myself until Fridays, so I could go with Aaron. I also hungered for that time.

Aaron would distribute the snacks and treats to the other kids when we got back to the house, and there was never a disappointed word.

All was good under the sun, dependably good, every Friday afternoon, without fail. I still have the grocery receipts.

When I recovered Aaron from the abduction in 2003, he was too ill to go shopping, and then he was ordered to return to Utah for deployment to Iraq, and then he became more ill there in Payson, and then came his Last Days.

To this day, I never enter a grocery store without thinking of Aaron, without feeling his absence, without remembering that last day that my family was safe, together and at home.

And then the Mormons entered the picture, and with them an abduction and a program….

child abduction,kidnapping,parental abductions

Aaron Cruz,

Aaron's Law,

ben and gina foulk,

chris and kory wright,

mormon abduction,

Payson Utah

Thursday, December 2, 2010

The last days of Aaron Cruz, pt 4: A terrible feeling...a note to mom....

By Sean Cruz

Portland, Oregon—

I awoke that April morning with a terrible feeling, with a sense that something dreadful was taking place. I was worried about Aaron, who was living in his mother’s empty house in Payson, Utah. He hadn’t answered his cell phone in several days, which happened from time to time and always caused me worry, and I considered calling the Payson police department to ask them to do a welfare check on my son.

There was an unknown element of risk to Aaron in getting the Payson PD involved, however, as I had little confidence that they could check on a person in crisis and not make matters worse, one way or another. There was much history where they had gotten things wrong in the past, this small-town Mormon police department on the edge of the desert, a story for another day.

I decided to try to get help from the Veterans Administration instead of the police, and when I arrived at my desk in the Oregon Senate that morning, I called Jim Willis, Director of Oregon’s Department of Veteran Affairs and told him about my worries. Jim assured me that they could help, that they could contact the Utah VA, that the VA does welfare checks on veterans in all sorts of crisis circumstances and that they do so frequently.

I was far more comfortable with the notion that my son would get a surprise visit from soldiers than from armed Mormon police officers, the same ones who had targeted Aaron for arrest in the past, more stories for another day. Payson is a small town with an infamous, lurid history, scene of non-Mormon settlers massacred by Mormons, polygamous horror stories, child brides marrying middle-aged Mormon men in the shadow of a powerful church.

Aaron did not fit in here, nor did his circle of friends, all rebels against the Mormon order, rebels without plan or leadership and bereft of resources, the local throwaway kids, every single one, some dying young from suicide and/or drug overdose, all sharing the same bleak shrunken vision of their own potential.

The local police were notoriously hostile to these kids.

Like any other parent, I was in the habit of worrying about my children whenever they were out of my sight, which in this ninth year since their 1996 abduction meant that worry was my constant companion, present in every breath of air, in every pulse through my heart, but today the worry was very strong and it was difficult to concentrate on my work. We were deep into the 2005 legislative session, but my mind was in Utah.

My fears were confirmed the following morning, when I received a call from the Payson Police Department. A friend of Aaron’s had grown worried about him and broke into the house, where he found my son lying unconscious on the floor.

This officer speaking to me had answered the 911 call, had found Aaron comatose in his mother’s house and as we spoke my son was in an ambulance on its way to the emergency room.

The officer told me that Aaron was unresponsive. I understood what that meant. He said that Aaron had apparently been there alone for three days, had not answered the door or his phone, and one of his friends had broken in and called the police.

He told me that they were unable to locate my son’s mother, so they were calling me. He gave me the hospital’s phone number.

The first time I called the ER, Aaron was in the elevator on his way up to that floor, the nurse said, to ICU, and she asked me to call back in 15 minutes.

When we spoke again, Aaron was in ICU, hooked up to the machines, but remained unresponsive. She gave me no cause for optimism.

I was on a flight to Salt Lake City early the following morning, paid for with money I had to borrow from friends. I had spent out all of my savings, leveraged all of my resources keeping Aaron alive over the past two years, and was now down to living from paycheck to paycheck.

I spoke into my son’s ear when I arrived at his bedside in the intensive care unit, “Aaron, it’s your Dad. Your daddy’s here, son,” I told him again and again. I don’t know if there was enough life left in him to hear me, but I know that hearing is the last sense to go, and I spoke into his ear. “I’m here, son, your Dad’s here, I will not leave you….”

I stayed with him for the next five days, sleeping either in a chair in his room or on a couch down the hall. I didn’t check into a motel until after they pronounced my beautiful son dead. Although he was on life support and technically alive in ICU, his fingers were stiff and his flesh hard, and I held no illusions about how this nightmare would turn out.

Hospital personnel met with Aaron’s mother and I on April 25. Aaron’s heart was strong, but there was no brain activity and no hope, and we agreed to end life support. Aaron was an organ donor, so they would need him for a couple of more days while they figured out what parts they could use to give life to someone else.

I clipped a lock of hair from the back of his head then and said goodbye to my son.

I left the hospital to see the place where my son had died.

The house was on a residential street near the center of town. No one was there. I saw where the door had been broken, and I walked inside.

The house was smaller than I had expected, with just two bedrooms on the main floor. A third room in the basement had apparently been used as a bedroom by my sons, but it was not up to code, with no fire egress. The walls and ceiling down there were painted black. It would have been a horrible place to live as a child, as a teenager. It was like a dungeon, this place where my children had been forced to live. The toilet in the basement bathroom had turned completely black. I’ve never seen anything like it. It must have taken months to get like that.

The only furniture was a bed and a couch, just stuff his mother had abandoned when she eloped with her fifth husband and moved out to El Dorado Hills, California, leaving Aaron behind. Years later, I would learn that Ben and Gina Foulk own and operate a string of senior care homes there.

There wasn’t much food in the house, and little to suggest that it had been a home recently. Cardboard boxes were stacked here and there, car parts and tools, clothes.

Wherever Aaron’s body had been lying when he was found had been cleaned up. There were no prescription bottles anywhere. Aaron would have had dozens of empty RX bottles. He never threw them out. He was a chain smoker. All traces of smoking were gone, too. No alcohol present. I was sure that Aaron had run out of his anti-seizure meds, but his mother had gotten there ahead of me and tweaked the scene.

I found a note in there, however, two pages long, written in Aaron’s hand on a yellow pad, and it read:

“In my hour of need, NO your not there

and though I reached out for you

you wouldn’t lend a hand.

“Through my darkest hour, grace did not shine on me

it feels so cold, so very cold, No one cares for me!

“did you ever think that I get lonely, did you ever think that I needed love,

did you ever think to stop thinking you’re the only one that I’m thinking of.

You’ll never know how hard I tried to find a space to satisfy you too.

“Things will be better when I’m dead and gone.

“Don’t try to understand, knowing you, I’m probably wrong.

“But oh how I’ve lived my life for you, still you turned away.

Now as I die for you, my flesh still crawls as I breathe your name.

“All this time I thought I was wrong, now I know it was you.

Raise your head, raise your face, your eyes tell me who you think you are.

“I walk, I walk Alone into the promised land, there’s a better place for me,

but its far far away.

“Everlasting life for me in a perfect world, But I Gotta Die first!

So please God send me on my way!

Time has a way of taking time. Loneliness is not only felt by fools.

“Alone I call to ease the pain of yearning to be held by you.

Alone so Alone I’m lost consumed by the pain!

I begged, I begged won’t you hold me again? You just laughed

My whole life was work built on the past, the time has come when all things shall pass

This good thing passed away….

“Don’t remember where I was when I realized life was a game.

The more seriously I took things the harder the rules became.

I had no idea what it’d cost, my life past before my eyes.

I found out how little I accomplished all my plans denied.

So as you read this know my friends, I’d love to stay with you all

Please smile when you think of me, my body’s gone that’s all

If my heart were still alive, I know it would surely break.

And my memories left with you there’s nothing more to say.

Moving on is a simple thing, what it leaves behind is hard

You know the Dead feel no more pain,

And the living all are SCARRED!”

On a third page, Aaron wrote:

“I heard somebody fix today, there was no last goodbyes to say

His will to live ran out, I heard somebody turn to dust

Looking back at what I left, a list of plans and photographs

Songs that will never be sung these are the things I won’t get done

Just one shot to say goodbye, one last taste to mourn and cry

Scores and shoots

The lights go dim, just one shot to do him in.

He hangs his head and wonders why, why the monkey only lies

But pay the pauper, he did choose

He hung his head inside the noose

“Ive seen the man use the needle, seen the needle use the man

I’ve seen them crawl from the cradle to the coffin on their hands

They fight a war but its fatal, It’s so hard to understand

I’ve seen myself use the needle, seen the needle in my hand”

Aaron’s notes were undated and unaddressed. With all of the changes to the scene, it would have been impossible to tell whether he had committed suicide, suffered some kind of overdose, or died from complications related to his seizure disorder, or through some other chain of events. The toxicology report had indicated no illegal substances were in his system, but he had lain there alone comatose in his mother’s house for three days, time for some metabolization to take place.

Two days after the end of life support, Aaron’s mother told her story about the last time she had seen him alive, about how he was sick and feverish and she had left him alone with a sack of groceries in that deplorable, ugly house, with some Heavenly Father stories to keep him company. The following week, at his grave site, she spoke about how she didn’t think Aaron would live long enough to move to Hawaii, but reassured the gathering that she had made him aware that Heavenly Father loved him, and I am still reeling from these disclosures.

The medical examiner would be unable to determine a cause of death. His mother wanted no further inquiry, and she and her new deep-pocketed husband Ben Foulk hired a law firm to prevent my access to Aaron’s medical records.

Reading my son’s last writing is heartbreaking, and five and a half years have gone by since his death, time when I could not bring myself to write a word about this part of the story of my son’s last days.

Aaron and I were very much alike. These notes show that he had a talent for writing and a willingness to write about very personal issues, about pain itself, that he was unafraid to reveal himself in a world where many people live in closets.

His reference to scarring could have meant the physical scars on his arms, the self-inflicted knife wounds that he had carved into himself not long after he had been taken into concealment in Utah, but could also have referred to the emotional scars that he and his entire circle of friends shared, living their lives of rejection in that isolated Mormon enclave, or both. He could have become a writer.

Although his note was addressed to no one in particular, there are a lot of people who put Aaron in this place and kept him there. A well-understood principle of the consequences of a criminal act is that a person who commits that act is responsible for every harm subsequent to the original crime, which was the abduction of my four children and their forced immersion into Mormonism in Utah.

For that reason, I will name each of those persons known to have participated in the abduction, a continuing crime with permanent consequences. These names are all permanently attached to the cause of Aaron’s death:

Mormons with no relationship to my children by either blood or marriage: Chris and Kory Wright, Bishop David Holliday, Bishop Donald Taylor, and Relief Society President Evelyn Taylor.

Micheletti family members and relations: Gina and Ben Foulk, Tony and Connie Micheletti and Cindy Anderson, and former step dad #2 Steve Nielson, the man who slapped my children around in Payson, Utah.

Those that consider committing the crime of child abduction need to understand that the consequences of “taking, enticing, keeping or concealing” a child are permanent. If you join in the plan, you are responsible for all that follows, until the end of time.

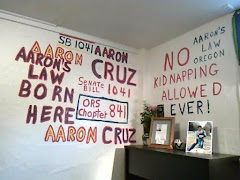

If you plan to take a child from Oregon, Aaron’s Law is waiting for you now….

To be continued….

Portland, Oregon—

I awoke that April morning with a terrible feeling, with a sense that something dreadful was taking place. I was worried about Aaron, who was living in his mother’s empty house in Payson, Utah. He hadn’t answered his cell phone in several days, which happened from time to time and always caused me worry, and I considered calling the Payson police department to ask them to do a welfare check on my son.

There was an unknown element of risk to Aaron in getting the Payson PD involved, however, as I had little confidence that they could check on a person in crisis and not make matters worse, one way or another. There was much history where they had gotten things wrong in the past, this small-town Mormon police department on the edge of the desert, a story for another day.

I decided to try to get help from the Veterans Administration instead of the police, and when I arrived at my desk in the Oregon Senate that morning, I called Jim Willis, Director of Oregon’s Department of Veteran Affairs and told him about my worries. Jim assured me that they could help, that they could contact the Utah VA, that the VA does welfare checks on veterans in all sorts of crisis circumstances and that they do so frequently.

I was far more comfortable with the notion that my son would get a surprise visit from soldiers than from armed Mormon police officers, the same ones who had targeted Aaron for arrest in the past, more stories for another day. Payson is a small town with an infamous, lurid history, scene of non-Mormon settlers massacred by Mormons, polygamous horror stories, child brides marrying middle-aged Mormon men in the shadow of a powerful church.

Aaron did not fit in here, nor did his circle of friends, all rebels against the Mormon order, rebels without plan or leadership and bereft of resources, the local throwaway kids, every single one, some dying young from suicide and/or drug overdose, all sharing the same bleak shrunken vision of their own potential.

The local police were notoriously hostile to these kids.

Like any other parent, I was in the habit of worrying about my children whenever they were out of my sight, which in this ninth year since their 1996 abduction meant that worry was my constant companion, present in every breath of air, in every pulse through my heart, but today the worry was very strong and it was difficult to concentrate on my work. We were deep into the 2005 legislative session, but my mind was in Utah.

My fears were confirmed the following morning, when I received a call from the Payson Police Department. A friend of Aaron’s had grown worried about him and broke into the house, where he found my son lying unconscious on the floor.

This officer speaking to me had answered the 911 call, had found Aaron comatose in his mother’s house and as we spoke my son was in an ambulance on its way to the emergency room.

The officer told me that Aaron was unresponsive. I understood what that meant. He said that Aaron had apparently been there alone for three days, had not answered the door or his phone, and one of his friends had broken in and called the police.

He told me that they were unable to locate my son’s mother, so they were calling me. He gave me the hospital’s phone number.

The first time I called the ER, Aaron was in the elevator on his way up to that floor, the nurse said, to ICU, and she asked me to call back in 15 minutes.

When we spoke again, Aaron was in ICU, hooked up to the machines, but remained unresponsive. She gave me no cause for optimism.

I was on a flight to Salt Lake City early the following morning, paid for with money I had to borrow from friends. I had spent out all of my savings, leveraged all of my resources keeping Aaron alive over the past two years, and was now down to living from paycheck to paycheck.

I spoke into my son’s ear when I arrived at his bedside in the intensive care unit, “Aaron, it’s your Dad. Your daddy’s here, son,” I told him again and again. I don’t know if there was enough life left in him to hear me, but I know that hearing is the last sense to go, and I spoke into his ear. “I’m here, son, your Dad’s here, I will not leave you….”

I stayed with him for the next five days, sleeping either in a chair in his room or on a couch down the hall. I didn’t check into a motel until after they pronounced my beautiful son dead. Although he was on life support and technically alive in ICU, his fingers were stiff and his flesh hard, and I held no illusions about how this nightmare would turn out.

Hospital personnel met with Aaron’s mother and I on April 25. Aaron’s heart was strong, but there was no brain activity and no hope, and we agreed to end life support. Aaron was an organ donor, so they would need him for a couple of more days while they figured out what parts they could use to give life to someone else.

I clipped a lock of hair from the back of his head then and said goodbye to my son.

I left the hospital to see the place where my son had died.

The house was on a residential street near the center of town. No one was there. I saw where the door had been broken, and I walked inside.

The house was smaller than I had expected, with just two bedrooms on the main floor. A third room in the basement had apparently been used as a bedroom by my sons, but it was not up to code, with no fire egress. The walls and ceiling down there were painted black. It would have been a horrible place to live as a child, as a teenager. It was like a dungeon, this place where my children had been forced to live. The toilet in the basement bathroom had turned completely black. I’ve never seen anything like it. It must have taken months to get like that.

The only furniture was a bed and a couch, just stuff his mother had abandoned when she eloped with her fifth husband and moved out to El Dorado Hills, California, leaving Aaron behind. Years later, I would learn that Ben and Gina Foulk own and operate a string of senior care homes there.

There wasn’t much food in the house, and little to suggest that it had been a home recently. Cardboard boxes were stacked here and there, car parts and tools, clothes.

Wherever Aaron’s body had been lying when he was found had been cleaned up. There were no prescription bottles anywhere. Aaron would have had dozens of empty RX bottles. He never threw them out. He was a chain smoker. All traces of smoking were gone, too. No alcohol present. I was sure that Aaron had run out of his anti-seizure meds, but his mother had gotten there ahead of me and tweaked the scene.

I found a note in there, however, two pages long, written in Aaron’s hand on a yellow pad, and it read:

“In my hour of need, NO your not there

and though I reached out for you

you wouldn’t lend a hand.

“Through my darkest hour, grace did not shine on me

it feels so cold, so very cold, No one cares for me!

“did you ever think that I get lonely, did you ever think that I needed love,

did you ever think to stop thinking you’re the only one that I’m thinking of.

You’ll never know how hard I tried to find a space to satisfy you too.

“Things will be better when I’m dead and gone.

“Don’t try to understand, knowing you, I’m probably wrong.

“But oh how I’ve lived my life for you, still you turned away.

Now as I die for you, my flesh still crawls as I breathe your name.

“All this time I thought I was wrong, now I know it was you.

Raise your head, raise your face, your eyes tell me who you think you are.

“I walk, I walk Alone into the promised land, there’s a better place for me,

but its far far away.

“Everlasting life for me in a perfect world, But I Gotta Die first!

So please God send me on my way!

Time has a way of taking time. Loneliness is not only felt by fools.

“Alone I call to ease the pain of yearning to be held by you.

Alone so Alone I’m lost consumed by the pain!

I begged, I begged won’t you hold me again? You just laughed

My whole life was work built on the past, the time has come when all things shall pass

This good thing passed away….

“Don’t remember where I was when I realized life was a game.

The more seriously I took things the harder the rules became.

I had no idea what it’d cost, my life past before my eyes.

I found out how little I accomplished all my plans denied.

So as you read this know my friends, I’d love to stay with you all

Please smile when you think of me, my body’s gone that’s all

If my heart were still alive, I know it would surely break.

And my memories left with you there’s nothing more to say.

Moving on is a simple thing, what it leaves behind is hard

You know the Dead feel no more pain,

And the living all are SCARRED!”

On a third page, Aaron wrote:

“I heard somebody fix today, there was no last goodbyes to say

His will to live ran out, I heard somebody turn to dust

Looking back at what I left, a list of plans and photographs

Songs that will never be sung these are the things I won’t get done

Just one shot to say goodbye, one last taste to mourn and cry

Scores and shoots

The lights go dim, just one shot to do him in.

He hangs his head and wonders why, why the monkey only lies

But pay the pauper, he did choose

He hung his head inside the noose

“Ive seen the man use the needle, seen the needle use the man

I’ve seen them crawl from the cradle to the coffin on their hands

They fight a war but its fatal, It’s so hard to understand

I’ve seen myself use the needle, seen the needle in my hand”

Aaron’s notes were undated and unaddressed. With all of the changes to the scene, it would have been impossible to tell whether he had committed suicide, suffered some kind of overdose, or died from complications related to his seizure disorder, or through some other chain of events. The toxicology report had indicated no illegal substances were in his system, but he had lain there alone comatose in his mother’s house for three days, time for some metabolization to take place.

Two days after the end of life support, Aaron’s mother told her story about the last time she had seen him alive, about how he was sick and feverish and she had left him alone with a sack of groceries in that deplorable, ugly house, with some Heavenly Father stories to keep him company. The following week, at his grave site, she spoke about how she didn’t think Aaron would live long enough to move to Hawaii, but reassured the gathering that she had made him aware that Heavenly Father loved him, and I am still reeling from these disclosures.

The medical examiner would be unable to determine a cause of death. His mother wanted no further inquiry, and she and her new deep-pocketed husband Ben Foulk hired a law firm to prevent my access to Aaron’s medical records.

Reading my son’s last writing is heartbreaking, and five and a half years have gone by since his death, time when I could not bring myself to write a word about this part of the story of my son’s last days.

Aaron and I were very much alike. These notes show that he had a talent for writing and a willingness to write about very personal issues, about pain itself, that he was unafraid to reveal himself in a world where many people live in closets.

His reference to scarring could have meant the physical scars on his arms, the self-inflicted knife wounds that he had carved into himself not long after he had been taken into concealment in Utah, but could also have referred to the emotional scars that he and his entire circle of friends shared, living their lives of rejection in that isolated Mormon enclave, or both. He could have become a writer.

Although his note was addressed to no one in particular, there are a lot of people who put Aaron in this place and kept him there. A well-understood principle of the consequences of a criminal act is that a person who commits that act is responsible for every harm subsequent to the original crime, which was the abduction of my four children and their forced immersion into Mormonism in Utah.

For that reason, I will name each of those persons known to have participated in the abduction, a continuing crime with permanent consequences. These names are all permanently attached to the cause of Aaron’s death:

Mormons with no relationship to my children by either blood or marriage: Chris and Kory Wright, Bishop David Holliday, Bishop Donald Taylor, and Relief Society President Evelyn Taylor.

Micheletti family members and relations: Gina and Ben Foulk, Tony and Connie Micheletti and Cindy Anderson, and former step dad #2 Steve Nielson, the man who slapped my children around in Payson, Utah.

Those that consider committing the crime of child abduction need to understand that the consequences of “taking, enticing, keeping or concealing” a child are permanent. If you join in the plan, you are responsible for all that follows, until the end of time.

If you plan to take a child from Oregon, Aaron’s Law is waiting for you now….

To be continued….

child abduction,kidnapping,parental abductions

Aaron Cruz,

Aaron's Law and child abduction,

ben and gina foulk,

chris and kory wright,

El Dorado Hills Senior Care Village,

Gina Micheletti,

mormon abduction

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)