By Sean

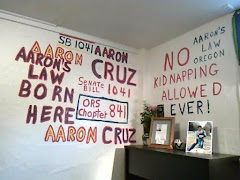

Aaron Cruz

Portland,

Oregon—

The

movie 12 Years a Slave shocked me a

bunch, but not for the reasons one might expect.

What

shocked me the most was not the bloody, detailed depiction of the barbarism and

cruelty of America’s Slave Era, because those facts are all well known, but in

the more subtle reaches: the forced separation of families, the scenes of Scripture-quoting

monsters in everyday life justifying their crimes against humanity, and in the other

parallels and contrasts I could see between Solomon Northrup’s experiences and

my own as the father of four kidnapped children whose abduction began some 18

years ago and continues beyond today, and in the attitudes we both encountered

along the way.

For

me personally, Solomon Northrup’s story was more about the present than it was

about the past, more about the pain of indifference than about the pain of the

lash.

I

went into the theater thinking about the horrors of slavery, but early on the movie

put me on a different course of thought: knowing first the suffering that lay

ahead for the Northrup family, the father losing his wife and children, and the

children suffering the sudden, mysterious loss of their father, and then during

the slave market scene, in the attitudes the slave Patsy encountered when she was

sold separately from her two children, never to see them again.

My

children and I were abruptly parted on February 12, 1996, when they disappeared

from Oregon in a kidnapping/shunning organized by Mormon church members in

Oregon, Washington and Utah, an abduction also intended to last forever.

My

mom never saw her grandchildren again, died four years into the kidnapping, an

extension of the shunning, how they disappeared from Grandma’s life, Mormons in

control, the indifference I encountered….

Three

different forms of abduction between us, I was thinking, sharing much in

common: Each was organized. There was planning and logistics and a larger social

structure that supported the crimes. Beyond their reckless disregard for life

and liberty, there was the kidnappers’ desire to do actual harm to a person

they did not personally know. The kidnappers’ actions resulted from their

respective religion- or race-based hatreds, and with which they intruded into

their victims’ lives.

My

first thought was that I would rather have been kidnapped into slavery than for

my children to be the kidnappees, that I would be beaten and chained in a box

if it meant my children would remain safe in their home, and that at least

Solomon Northrup knew that no one was tricking and tormenting his children

during the captivity, deliberately destroying every emotional as well as

physical link between them and forcing his children into complicity in the

kidnapping. And none of his children died during the course of his ordeal. It

could be worse, I thought, than this. I would take those beatings, and 12 years

of separation is much better than 18.

In

the slave market scene, a slave trader told Patsey in not so many words that

she would forget about these children sooner or later, so she ought to move on

and focus on her new life with the new master, and I found myself saying out

loud to no one in particular, “That’s what they expected me to do, too.”

I

was referring to the attitudes I have encountered. People have been telling me

this ever since the beginning of the abduction, that I ought to “move on” or “accept

this”, in one way or another, and my children’s kidnappers were all of this

mind also, believing that they could get away with their crimes if I did move

on, and for so long as they could continue to maintain control over my children’s

lives, which they do even as adults.

The

larger society was indifferent to all of these abductions as they were taking

place. Years went by before Solomon found a person willing to get out of his

comfort level and take an action that would lead to resolution and

reunification, if not justice. It was not wishing or hoping or praying or

pissing up a rope that brought the Northrup kidnapping to an end, but a person

taking action.

In

all of the 18 years of the Cruz kidnapping, I only encountered one such person,

a retired police officer named John Bissell, who saw the situation for what it

was and did everything he could to help.

But

I don’t believe that anyone in the movie’s audiences would expect Solomon to

ever do this, to move on or accept these injustices, a contrast between our

experiences that arises from people’s attitudes entirely, although we do know

that Solomon was in fact reunited with his children. No one knows, however, if

the Cruz abduction/shunning will ever come to an end, if the Mormons will ever

release my children to have contact with their father again, he who dared to

criticize LDS doctrine in his own home….

Scripture-thumpers

dominate both of our stories. Sunday worshippers committed the crimes against

the Northrup and Cruz families, pious slavers and prayerful shunners, each reading

from their Good Books the lines that made fit their crimes. Woe be to those who

disagree with The Teachings that justify our respective Peculiar Institutions;

punishments of Biblical proportions resulting, they intone in their Psalm-singing

and Tabernacle Choirs….

18

years of painful separation, so far, 18 years a kidnapping, and a whole church

to keep it that way….

------------------

Coming soon:

12 Years a Slave – 18 Years a Kidnapping,

pt 2.

Our

stories also have in common the heartlessness of the abrupt break in

communications between parent and child that the kidnappers impose. Solomon and

Patsey had no way to contact their children as years went by, and my children’s

Scripture-quoting kidnappers were able to cut off every means of communication I

was ever able to establish between us as I fought through four jurisdictions in

three states.