By Sean Cruz

Portland, Oregon—

“Guns drawn, everyone out and down on the ground!”

That’s how the officer described what would happen if the police encountered whoever was driving my freshly-stolen car, just last week.

He wanted me to know this because, although finding the car myself would be extremely unlikely, it does happen, and if I did happen to find it, I should report that fact before driving it anywhere, because I could also find myself facing an abrupt out-of-the-car-and-down-on-the-ground-at-gunpoint situation, and however unlikely that might be, it would be good advice to keep in mind.

Less than two hours after I had reported it stolen, information about my recently-departed red Subaru was already in the Law Enforcement Database and police agencies had been alerted from the Canadian border down to Mexico, and from the Oregon coast eastward to the Mississippi River.

As I listened to the officer, I reflected back nearly fifteen years ago, when I had reported the disappearance of my four children to local law enforcement, taken in what I would learn was a Mormon abduction as much as it was a parental and family abduction, and how differently law enforcement handled the case.

The bottom-line point I want to make here is that while Oregon law enforcement agencies maintain and share lists of stolen vehicles, there is no comparable list of abducted children anywhere throughout the state.

This dichotomy exposes one of the major gaps that abducted children fall through, particularly if the suspected kidnapper is a parent or family member.

The structural problem lies in the fact that local law enforcement agencies handle each case of abducted or missing children in their own way, with little or no sharing of information with other agencies or with the Oregon State Police Missing Children’s Clearinghouse.

The OSP Missing Children’s Clearinghouse has added only one new name to its short list in the past three years.

The Senate Interim Task Force on Parental and Family Abductions became aware of the problem in 2004 and considered legislation to correct it, but was dissuaded as reported to the Senate President:

“The Task Force considered legislation that would have required that all local law enforcement agencies report missing children to the Oregon State Police Missing Children’s Clearinghouse.

“However, after the State Police and the Department of Justice met and discussed the issue, they determined that the State Police could obtain this information by an administrative process that will automatically notify the Missing Children’s Clearinghouse of all reports of missing children made by state, county and local law enforcement agencies. Consequently, the Task Force decided that this legislation is not needed.” –Final Report, Senate Interim Task Force on Parental and Family Abductions, 2004.

It is important to understand what is being stated here:

1. The Task Force wanted to require that all Oregon local law enforcement agencies report all cases of missing or abducted children to the OSP Missing Children’s Clearinghouse, because they were not doing so on their own.

2. The OSP stated that they could get the information from local law enforcement by administrative rule, convincing the Task Force not to press legislation.

3. The OSP never implemented the rule, which would have created a list of all cases of abducted or missing children reported in Oregon.

The Task Force determined that Oregon has its per capita share of the more than 200,000 cases of parental and family abductions that take place in the USA each year, yet the Oregon State Police has added only one name, that of Kyron Horman, to its Missing Children’s Clearinghouse list in the past three years.

A few months ago, a father from southern Oregon whose 3-year-old daughter went missing with the child’s mother in July contacted me. Local law enforcement had told him that his missing child did not “meet the criteria” for any actual action by law enforcement, including adding his missing child to the State Police list of missing Oregon children, or notifying law enforcement in other jurisdictions of the missing child…and yet there was a child missing….

The phrase “does not meet the criteria” struck me when I took the call, because I was already planning to write about the subject, which came up during a press conference on the Kyron Horman abduction on July 23, when Sheriff Dan Staton

responded to a series of questions, including this one:

Q: How many other children are considered missing/endangered in Multnomah County at this time, aside from Kyron?

“There are no other cases that meet this criteria,” he said.

“This criteria” may have included the fact that one of Kyron’s close family members is a police detective, giving the family instant credibility with law enforcement.

Coupled with the fact that Kyron’s disappearance was originally thought to be a stranger abduction (since no one else was missing), the family’s call to 911 quickly led to the largest search for a missing child in the history of the state.

The OSP could hardly ignore that.

The Oregon State Police Missing Children Clearinghouse maintains a list of abducted or otherwise missing children, which stands currently at 41 children.

More than half of these children have been missing for decades, and the only child that has “met the criteria” to make the OSP list in the past three years is Kyron Horman….

The US Department of Justice has reported no decrease in the number of abducted children, tallied at more than 200,000 annually for more than a dozen years, signaling that not enough is being done to address the problem.

People abduct their own children or other family members in large part because they are likely to get away with it, to suffer no consequences for their part in the crime, partially explaining why the number is so high.

The failure of law enforcement to utilize the same technological resources that enable them to instantly notify agencies across every jurisdictional level or locale about my stolen Subaru, to reach the same agencies with reports of abducted or missing children is difficult enough to understand.

The Task Force report documents the fact that OSP and the Department of Justice became aware of both the problem and the solution through the course of the Task Force’s work, and yet have done nothing to correct it.

We all live complicated lives. Imagine for a moment how complicated your life would be if your child was abducted, and you found out that your child’s’ name wasn’t on the list, because there was no list.

It is not a question of knowledge or awareness; the Task Force report and the OSP’s addition of just a single name in the past three years indicates that this is a problem of policy, a problem of priorities, a matter of choosing to value stolen property over stolen lives.

--Sean Cruz, November 2010

Thursday, November 4, 2010

Abducted child vs stolen car: A problem of priorities

child abduction,kidnapping,parental abductions

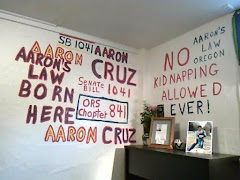

Aaron Cruz,

Aaron's Law child abduction,

ben and gina foulk,

chris and kory wright,

Kyron Horman,

Oregon State Police

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment