from The Oregonian, Margie Boule, June 4, 2006

Abducted by parents, children become the forgotten victims

Even today, 29 years after she was abducted and lived in hiding with her mother, she sometimes can't figure out who she really is.

Is she Liss Hart-Haviv, who lives in Kalama, Wash., and heads up a well-respected national organization for adults who were abducted as children?

Or is she Missy Sokolsky, who grew up in an affluent family on Manhattan's Upper West Side, attending private schools, taking ballet, piano and riding lessons?

Or is she Melissa Hart, who spent part of grade school living in a single room with her mother in a rundown neighborhood in San Diego, surviving on charity food, learning to lie and being afraid of anyone in a uniform?

Liss admits she hasn't yet recovered from the sudden, dramatic disappearing act her mother forced upon her when she was 11 years old. "I spent part of my childhood on the run from a parent," she says. "Then I spent the rest of my life on the run from my childhood."

This story may change the way you look at child abduction. Maybe you see it as a simple child custody issue. Or maybe you remember the devastated parents on TV shows. But almost nobody thinks about what the abducted child is going through, according to Liss and other survivors of abduction who've created Take Root, an organization to provide support and advocacy for abductees.

After what Liss refers to as the "hug and go" reunions in front of cameras, with cheering relatives engulfing the returned child --nobody thinks about what the child goes through after being returned to left-behind family members who've become strangers.

Often when Liss talks about the little girl she was before she was abducted, she uses the third person. She doesn't say "I loved my father." She says, "Missy loved her father." It's as if Missy died the day her mother took her away.

She was born in New York, "the daughter of an attorney and a Southern homecoming queen." Her parents divorced when Missy was 3. She lived with her mother, but her father always was around.

Unfortunately, he was a troubled man. "He was an alcoholic with emotional problems," Liss says. "He was very wealthy and powerful and obsessed with my mother. He really made her life a living hell." Liss says her dad "called the apartment 30 or 40 times a day. When her mom didn't pick up, he'd come and pound on the door in the middle of the night.

"And he'd withhold child support. The courtroom was his playground, a way to see my mother if she was constantly in court over child support or alimony."

When Liss was 9, her mother snatched her and ran to Florida. Liss' father hired detectives, and snatched Liss back. On the way back to New York, her father took a two-week detour to New Orleans. With uncombed hair, wearing the same dress, Liss sat in bars while her dad partied.

"He was not equipped to raise a 9-year-old girl," Liss says.

A few months later, her mother snatched her again.

"That was the end of Venetia and Missy Sokolsky," says Liss. "From that day forward those two people ceased to exist. And on the other side of the country, in San Diego, Sharon and Melissa Hart appeared out of thin air. . . . She changed our identities."

They had no contact with anyone they'd known before. Liss left behind friends, relatives, toys, pets and her father. She was told her father would hurt her mother if he found them. "It was a life of hiding and terror."

Liss believes her mother "really had my best interests at heart." But no matter what the parent's motivation, Liss and other former abductees believe abduction is not the answer. "A child taken into isolation with a distressed caretaker is never in a safe situation, no matter what the parent's intentions," Liss says

Take Root would not exist if Liss hadn't heard the term "child abduction" on a radio show. She went home, did an Internet search and discovered she was far from alone. "Over 200,000 children are abducted by a family member or parent every year," she says. The realization "unlocked the strongbox I had stuffed everything into; all the grief from that moment of abduction, when Missy Sokolsky disappeared. I wept and wept."

She realized she needed help. But every agency she could find was created to aid parents of missing children. "The parents were perceived as the victims, not the children. . . . There were no mental health professionals with expertise on long-term impact. No research has been done. Finally, in utter frustration, I called the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. I said, 'With a name like that, how can you have nothing for the missing children?' And their response was, 'You are exactly right.' "

The organization funded a meeting of nine adults who'd been abducted by parents when they were children. They met in Alexandria, Va., in 2001. Before the meeting, "I was somewhat skeptical that we really had common ground," Liss says.

She was wrong. All had felt alone. All had struggled after their "recovery." And all continued to be scarred by the abductions.

Liss' father found Liss and her mother after two years in California. But by then her father had "really gone over the edge." He'd "lost his job, and done nothing but drink and obsessively look for us." He knew he was in no condition to raise her, Liss says. So she stayed in California, occasionally visiting her dad in New York.

The visits were rocky. Liss, who kept the name Melissa Hart, wanted to talk about her new life. Her father wanted back the child who'd left, but she didn't exist anymore. "Conversations with him were all about his devastation and attacks on my mom."

Today Liss' relationship with her mother is "a work in progress," Liss says. When Liss points out there were other ways her mother could have handled her father's obsessive behavior without abducting Liss, "she gets defensive and explodes," Liss says.

Unfortunately, Liss wasn't able to mend her relationship with her father before he died. But she's forgiven him, "because he's not the one who created, for me, the real trauma, which was the loss of Missy Sokolsky."

After difficult teen years, Liss pulled her life together and graduated as valedictorian at University of California, Berkeley. As head of Take Root, she's testified before Congress and appeared in the national media.

Take Root (www.takeroot.org) already has changed a lot of people's perspectives about the world of missing children. Groups that once only created search plans now are considering recovery plans for abducted children.

Take Root has created protocols for police, mental health professionals and reuniting families to help returning children integrate their different identities.

"We want to build something constructive out of our experiences," Liss says. "We want to transform victims to victors."

Contact Margie Boule: 503-221-8450, marboule@aol.com

Thursday, May 8, 2008

Abducted by parents, children become the forgotten victims

child abduction,kidnapping,parental abductions

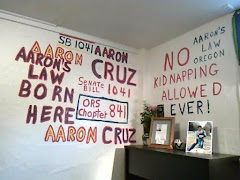

Aaron's Law and child abduction,

Columbia Ultimate Business Systems,

CUBS Vancouver,

custodial interference Oregon,

kidnapping,

Mormon kidnapping,

Oregon law on kidnapping,

parental abduction,

Parental abduction Oregon,

stop parental kidnapping

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment