This column by S. Renee Mitchell appeared in the Oregonian on October 24, 2005. (my comments are appended at the end)

It took almost 10 years, but Sean Cruz has finally learned to live with his unrelenting heartbreak.

He's sleeping more at night. The bouts of depression are as familiar as a friend, but thoughts of suicide don't visit as often.

"When your child is gone, every minute is impossible," Cruz says. "You're trying to get through the day. You can't sleep. Your food has no taste . . . Whatever was going on, I just couldn't deal with it."

On Feb. 12, 1996 -- in the middle of a winter storm -- Cruz's ex-wife took his four children, ages 8 to 17, and shuttled them through family homes in different states before ending up in Utah.

Cruz, who has joint custody, contacted police, who couldn't help. He hired lawyers he couldn't afford. And he regularly sent lengthy e-mails to people like me who saw his name and pushed the delete button.

"You assume that people are going to hear you when you say, 'My child was abducted,' " says Cruz, an aide to Sen. Avel Gordly. "But the word 'abduction' or 'kidnapping' seems to make people uncomfortable."

Cruz couldn't get regular access to his children until 2003, when his oldest son, Aaron, who was fighting a meth addiction, moved to Portland. (see correction, below)

After three months, though, the 21-year-old returned to Utah, hoping to be reunited with his younger brother, who is on his second tour in Iraq. But Aaron, who suffered from insomnia, depression and anxiety, was too sick.

In late April of this year, Aaron slipped into a coma and died. After the funeral, Cruz says, his daughters, now ages 26 and 17, stopped returning his phone calls. Cruz hasn't heard from his other son, age 21, for two months.

"It's like the kids got swallowed up again," says Cruz, whose laugh lines have been widened by years of worry and regret.

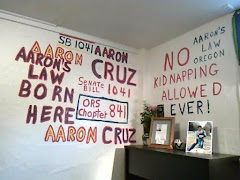

Without his children, Cruz's focus became fighting parental abductions. He persuaded Gordly to push legislation -- called "Aaron's Law" -- that gives families tools to punish parents for the crime of child abduction. The House, led by Rep. Linda Flores, R-Clackamas, unanimously approved the bill in the last week of the session.

"Aaron's Law" lets the courts appoint legal and mental health advocates for any minor children, even before a criminal or family law case goes to court. Aaron's Law also permits any adult or child to sue for financial damages against any person who interferes with a court's custody order.

The law -- which had at least 10 revisions before final passage -- recognizes that abducting a child is abusive. Children are traumatized when they suddenly lose access to everything that's familiar, says Liss Hart-Haviv, of Take Root, a Portland-based nonprofit that advocates for abducted children (www.takeroot.org).

"The loss and the grief that the child experiences is really difficult to get your mind around," Hart-Haviv says. "It doesn't really matter who takes you or what their motivations are, it's still the experience of being abducted."

Aaron's Law also is leading to a statewide symposium where Oregon can create a systematic approach to preventing child abduction. It also includes training to encourage law enforcement officials to take the crime seriously. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, more than 200,000 children each year are kidnapped by a parent or family member.

"This is a story of how the process can work," Gordly says. "Sean put his heart and soul, everything he had, into not just the bill but educating me and educating other legislators about the damage that happens to children who are abducted."

Although Aaron's Law will help other parents, Cruz's suffering will probably never end. He can never recapture all that he has forever lost. And his troubled mind can't seem to find complete peace -- even when he sleeps.

"I mourn Aaron's death," Cruz says. "But I also mourn the last 10 years of his life. I just can't imagine that."

-----------

Sean's comments: Aaron wasn’t fighting a meth addiction. He was in a methadone program, fighting an opiate addiction that originated with the heavy medication he was prescribed after he was taken to Utah. Before he was taken, Aaron was completely healthy. Afterwards, however, he suffered from major clinical depression, chronic insomnia and severe anxiety.

From the age of 15, the adults surounding him in Utah dosed him with Ritalin, Alderol, Prozac, Zoloft, Xanax, Oxycontin and other drugs ( I have not been able to gain access to his complete medical records yet). At the time of his death, Aaron had been medicated continuously for nearly the entire time since he was taken from Oregon. It is common for abducted children to lose access to medical care. In Aaron's case, the medical providers appear to be linked to the church leaders involved in his abduction.

He put himself in a methadone program, trying to regain control of his life, in 2003. He told me that his dream was to work at my side in the legislature. That was my dream as well.

He was undergoing medical tests here in Portland, where we were trying to gain an understanding of his physical and mental health problems, which included a serious thyroid problem and the seizure disorder which led to his death, when he received orders to report to Utah for deployment to Iraq.

Despite a life-threatening condition, Aaron left unhesitatingly for Utah to join his brother for deployment (Army National Guard). He came downstairs as soon as he received notice of the orders and said, "Dad, I'm going to join my unit. I've got to look after my brother."

A few days later, on Thanksgiving 2003, I watched him pack, and the next day he was gone.

When he left my home, his access to competent health care ended.

It is also incorrect to state that the children were taken by my ex-wife. It was a child-stealing ring motivated by extreme bigotry that enticed, tricked, took and kept the children. And it was in their interests that Aaron was kept quiet and under control through medication and indoctrination. The known members are named in earlier posts to this blog.

postscript: Aaron refused to accept the severity of his illness and never gave up trying to join his brother. He believed he could get well in Iraq if he was given a chance. Shortly before he was stricken, Aaron called me and said, "Dad, I'm going to Iraq. I'm joining the Marines. They're looking for people just like me."

And he was right, the Marines do look for people just like him: courageous, selfless, ready to serve and never--ever--willing to give up.

It runs in the family.

Thursday, May 8, 2008

A man works through loss for others' gain

child abduction,kidnapping,parental abductions

Aaron's Law and child abduction,

Columbia Ultimate Business Systems,

CUBS Vancouver,

custodial interference Oregon,

kidnapping,

Mormon kidnapping,

Oregon law on kidnapping,

parental abduction,

Parental abduction Oregon,

stop parental kidnapping

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment